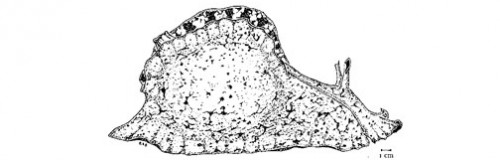

Meet Aplysia californica, the sea slug whose starring role in the history of neuroscience was a revelation when I started reading about the brain.

“Aplysia californica” is the first piece I published from my memoir, The One You Get: Portrait of a Family Organism. The book is a portrait of an artist as a biological and social organism, raised by hippies in the petri dish of 1970s southern California, in the wake of my family’s lost wealth and celebrity. The essay will give you a taste of the book–and how I use my own unforgiving memory, my family’s hysterical mythology, and biological research to tell the story of my childhood.

Without giving too much away, I can tell you that I encountered a slew of these slugs on a southern California beach when I was a kid. The slugs showed up to console me at a moment when I was feeling particularly oppressed by hippie life and the converted schoolbus we lived on. For twenty-five years, I’d been under the self-centered impression that this creature’s only starring role was in my own development. It turns out that day on the beach was just a cameo performance for Aplysia. The neuroscientists discovered sea slugs long before that day and have studied them continuously for many decades.

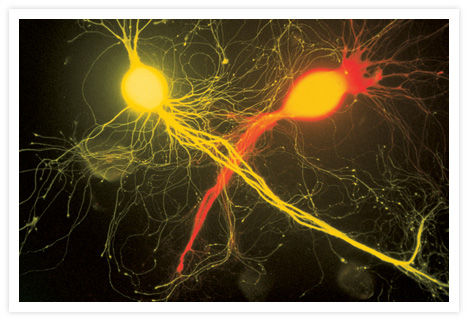

This is a rendering of Aplysia’s neural architechture, whose simplicity has made my beloved slugs such valuable laboratory subjects.

Those glowing onion creatures are a couple of Aplysia neurons, presumably cut from the abdomen of some poor slug, where you can find colonies of nerve cells that comprise something like a simple brain. The cells are huge—nearly a millimeter—which makes them easy to see and study. The neuroscientists have injected these cells with dyes to make them glow like celestial bodies. This is just one of many examples of the artistry entangled with doing day-to-day science. But of course with the artistry comes violence. Like curious kids, the neuroscientists poke and prod the slugs, they induce pain, they kill them, they slice them up into cross-sections, they excise their nerves—all in the name of learning something about how brains work.

Without the violence, Aplysia’s neurons wouldn’t glow or be colorful. In this case, the dyes help reveal a basic fact: the cells are involved in many overlapping jobs. (You might say these jobs are entangled.) They help us see where their axons and dendrites hook up, giving and receiving input from each other. When I look at this image as a non-scientist, I see metaphors. The onion creatures cry out for comparisons between acrid layers and the layered processes favored in the brain. The glowing orbs, like primary-colored comets gliding some solar system, hint at the contiguities of form that prompt the mystically inclined to find unseen harmonies among solar systems and organisms, among planets and sea slugs. I like thinking about this kind of thing too, but I don’t like drawing conclusions about where we came from or what it means. I’d rather let the apparent harmonies be mysterious, and I’d have to insist that we take stock of the violence involved in our quest to see them.

But my relationship to sea slugs isn’t mystical, grand, or mysterious. It’s about identification–okay, projection! I love those slugs, and I want to believe they loved me back. But I also wanted to be them and wanted them to be me, at least for an afternoon.