There is no cooler place than Lou’s Records in 1983, 84, 85. Not anywhere. We could flip through these records until infinity.

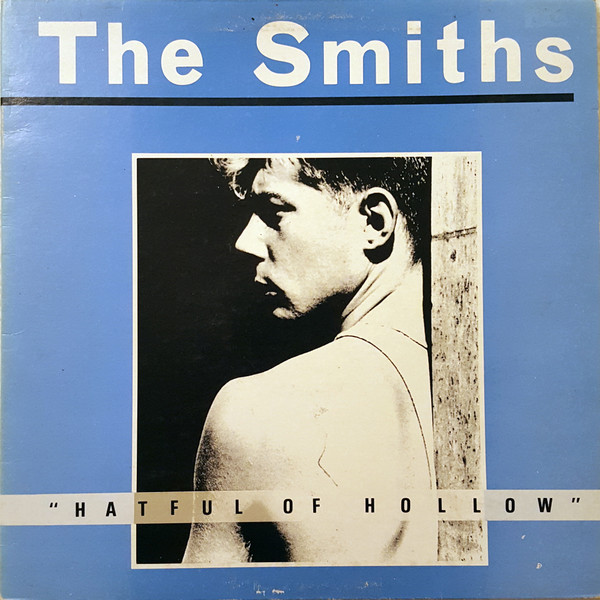

I like a slow flip, so I can really feel the soft tap of the thick plastic Lou’s puts on every record. I’m looking for David Sylvian records, and I know the real supply is waiting in Imports, but there’s a lot to learn at Lou’s. They’re playing The Smiths’ Hatful of Hollow, have been since we came in. I recognize my dissatisfaction in Morrissey’s wail the second I hear it. “A boy in the bush is worth two in the hand.” There are posters and album covers papering every inch of wall space, and right now Hatful of Hollow is displayed in the center of the ceiling, pasted over posters of The Cure, Social Distortion, Haysi Fantayzee, Everything But the Girl, Echo and the Bunnymen, The Dead Kennedys, Fad Gadget. It’s a huge light blue poster, with a simple square near the bottom containing a black and white photo of a handsome but weary man-boy with a messy fifties fade and wifebeater.

I get to the plastic divider with The Smiths written in blocky blue magic marker. There are only two LPs here, Meat Is Murder and The Smiths, with their blocky type, black and white images of shirtless boys and reluctant soldiers. I can see the record cover sitting on the Now Playing shelf, so I know this is it. It should be here.

I can see Shannon talking to the girl behind the counter with the black bob, the side pinned back with a tortoise shell barrette, the pale skin, powder making her freckles seem transparent, and silver ring in her nose. She’s wearing a white t-shirt, black cardigan, and pleated plaid mini-skirt with black tights. Shannon is a girl we met through Amy Buzick, at the Carlsbad Mall, and though we don’t know how long she’s been Newro, she wears it like it’s been years. She’s sixteen, but she’s not afraid to talk to a girl like this, who is at least 19, works at Lou’s, and has clearly passed through the phase we’re in and come out the other side much cooler and at ease with her look. “I’m looking for the remix of ‘You Spin Me Round’ by Dead or Alive,” Shannon says. “The import version.”

“We had two copies,” she says, without looking up from the records she’s pricing, “but we sold them.”

“Do you know when you’ll get more?” she asks.

“Maybe Tuesday.” The pink stone in Shannon’s nose glinting two feet away from the black-bobbed girl’s silver ring sums up the differences between them: spiked and matted white and pink mess to shiny black bob; crisp white t-shirt and soft cardigan to tatty old lady’s silk blouse with puffy sleeves; knee-length army issue wool skirt (even though it’s eighty-nine degrees out) to pleated mini, Doc Marten boots to platform patent leather shoes. This girl is out of our league, but Shannon behaves as though she believes strongly that she’s got what it takes to be drafted.

Paul’s got his arms full of import Cure records. Tiffany, a girl we know from elementary school who just moved back with her head shaved all around except for long nearly white bangs hanging in front of her face, is holding records we would never buy: Social Distortion, Dead Kennedys, Christian Death. I’ve chosen David Sylvian’s solo record, Brilliant Trees and Japan’s live album Oil on Canvas. The Smiths record has finished, and the guy behind the counter, fat with a green Mohawk and multiple rings through his eyebrows, is putting something else on: Ministry. Paul looks up. He loves Ministry.

There’s a cute guy in Import T. He’s got flame red hair, brown skin like maybe he’s Mexican under the make up, and blue plaid pants with a sleeveless mesh black t-shirt, and big army boots. He’s probably 18. I want to squeeze into Import S, but I settle for M and wait. I flip and read: Madness, glance out of the corner of my eye at the boy. Flip, read: Magazine, glance. Flip, read: Meat Puppets, glance. Flip, read: Mink De Ville, glance. He’s leafing very slowly through the Rs and moving onto the S section, so slowly you don’t even hear the plastic tap: Modern English, New Order, Pet Shop Boys, Q-Feel. Glancing.

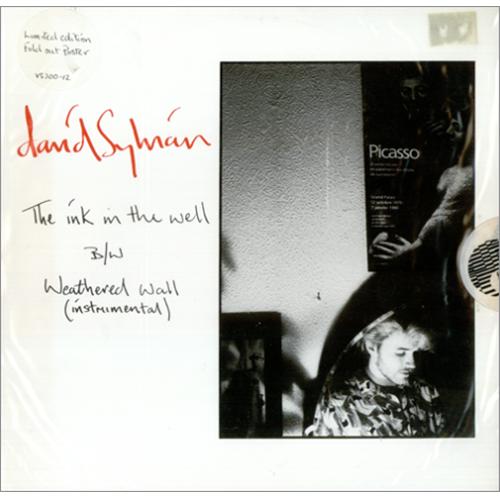

When the cute guy finally moved to U, I can safely make a leap to S. I flip to the end first, to Sylvian, and there’s what I want: The 12” single of “The Ink in the Well,” whose cover folds out into a free poster of David Sylvian lying in a dark room like he’s in an enlightened coma. I add it to the records in my pile, and flip back, slowly enough to make it look like I’m really reading every record, until I get to The Smiths. I see the light blue spine first, behind to 7” singles, mounted on cardboard, then the black and white photo. The record cover is thick. It folds out. I pluck it and look up. Green Mohawk is turning Ministry over. Paul is nodding along to it, deep in Import G. I back up and look at 12”s by The Smiths They belong to the same black-and-white, blocky-typed universe of sad and pretty men struggling with their feelings under dreary English skies. “What Difference Does it Make?” features a smiling guy in a cardigan toasting with a glass of milk and “How Soon Is Now” a guy sitting on the edge of his bed in his underwear, dark hair mussed, face in his palm.

Tiffany and Shannon are at the register. I follow them there. “Paul,” Tiffany says. “Speed it up.”

“Almost,” Paul says, finishing the Gs.

Shiny black bob rings each of us up, recording the title, ISBN, and record label of each purchase. Shannon’s got all 12” singles. She’s known for being a good dancer. Tiffany has all hardcore. I have Japan and David Sylvian and The Smiths. Paul has all Cure, most of it early, all of it import. Black bob documents it all without smiling or glaring or showing any response or judgment. I almost wish she would so I’d know what she thinks or likes.

“Let’s walk to the beach and look at the records,” I suggest when we get out onto the sidewalk.

“I have to meet my sister,” Shannon says, not offering where or how. We all know her sister April is 18 and has a car and a punk boyfriend. Shannon disappears down the sidewalk and the rest of us walk the block and a half to the beach, where we sit in our heavy clothes and slide our records from their plastic. People are packing up, dragging their towels past us, shaking their heads at our inappropriate choice of dress. The sun wobbles over the horizon, turning orange.

“What time is it?” Tiffany asks. We don’t have watches, so we can’t say. “Excuse me,” she says to the family of four passing with their picnic basket, “Do you have the time?”

“5:45,” the mom says.

“Fuck,” Tiffany says, loud. The family of four speeds up. “I’m so fucking dead. My mom said I had to be home by 6 no matter what.” The mom and dad whisper to each other and turn the corner.

We slide our records back in plastic, fumble with our bags, sink our boots through sand, climb the steps to the street, and walk our fastest to the corner, where the bus stops. We want the No. 19 bus, which runs directly from K-Mart in Escondido to the Encinitas corner where Lou’s is.

“We just missed the 5:49,” Paul informs us.

“Don’t they run every half hour?” I ask.

“Not after six. It’s every hour now.”

“So we have to wait until 6:49?” Tiffany asks. “I’m a corpse.”

“Let’s find a pay phone,” I say. “Who has quarters?”

“I have some bad news,” Paul says.

“What?” I ask.

“It skips an hour. The next bus is at 7:49.”

“That gets us home at, like, 9,” I say.

“Fuck,” Tiffany says. “I’m a corpse.”

This is a deleted scene from The One You Get: Portrait of a Family Organism (Dzanc Books)