At twelve, Ralph is a tiny party writhing under the heavy hands of frustrated nuns.

St. Vincent’s School for Boys in San Francisco doesn’t suit him. Most of these boys got here through a petty crime, their own or their parents. For others it was a parent’s suicide or murder. For Ralph, it was his father’s schizophrenia. When he was finally locked up for good, his mother couldn’t handle both him and the two girls, so he became an orphan with two living parents.

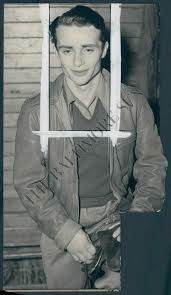

In 1960, a reporter for Coronet magazine will describe the adult Ralph—at 4’11” and 109 pounds—as “a trim little party

with inky hair, snapping dark eyes, olive skin and handsome Valentino features.”

At twelve, Ralph’s already the ringleader, surrounded by a band of boys, a wad of tobacco longer and wider than his tongue stuffed between his cheeks. He hears Sister Agnes’s bellow at the precise moment the dice spring from his palm: “Ralph Neves!”

He grins. “Want a piece of the action, Sister?”

“Spit that out,” she replies, “immediately.”

Ralph spits the contents of his tiny mouth all over the short-sleeved white shirt of the doughy blonde kid next to him.

“That’s it, Neves” is all Agnes says, yanking his arm. Ralph relaxes his body until it’s just a pile of flesh, forcing the nun to drag him like a cadaver. The boys, including the doughy blonde, watch with the fear that should be in Ralph’s eyes. Ralph delivers a wide grin, not fixing on anybody in particular, making sure they all enjoy his triumph.

It was only a matter of time, and he wants to leave them with something to remember, so that night Ralph jumps out his second story window, climbs a seven-foot wall and wanders through a forest of oaks until he finds an empty shack, where he sleeps, living on bread and apples he coaxes from some local kids who play in the forest. The kids make a project of the runaway. He swears them to secrecy, and for six days they bring him food and reports about the police search for him. On that sixth day, there is no report. It’s odds enough for Ralph, and the next day, when the kids find the shack empty, they agree the scrawny runaway must have wandered off to die.

In a few years, they’ll read about the Portuguese Pepper Pot, who made his way from San Francisco to a horse ranch up north, where he learned to command thoroughbreds. They’ll read about his string of wins at Santa Anita, his penchant for using his horse as a weapon to knock other jockeys off theirs, the day he sealed his “fuck ’em all” motto by showing up on the track in a hospital gown an hour after an announcer enjoined the crowds in a moment of silence to mourn his death after a brutal fall.